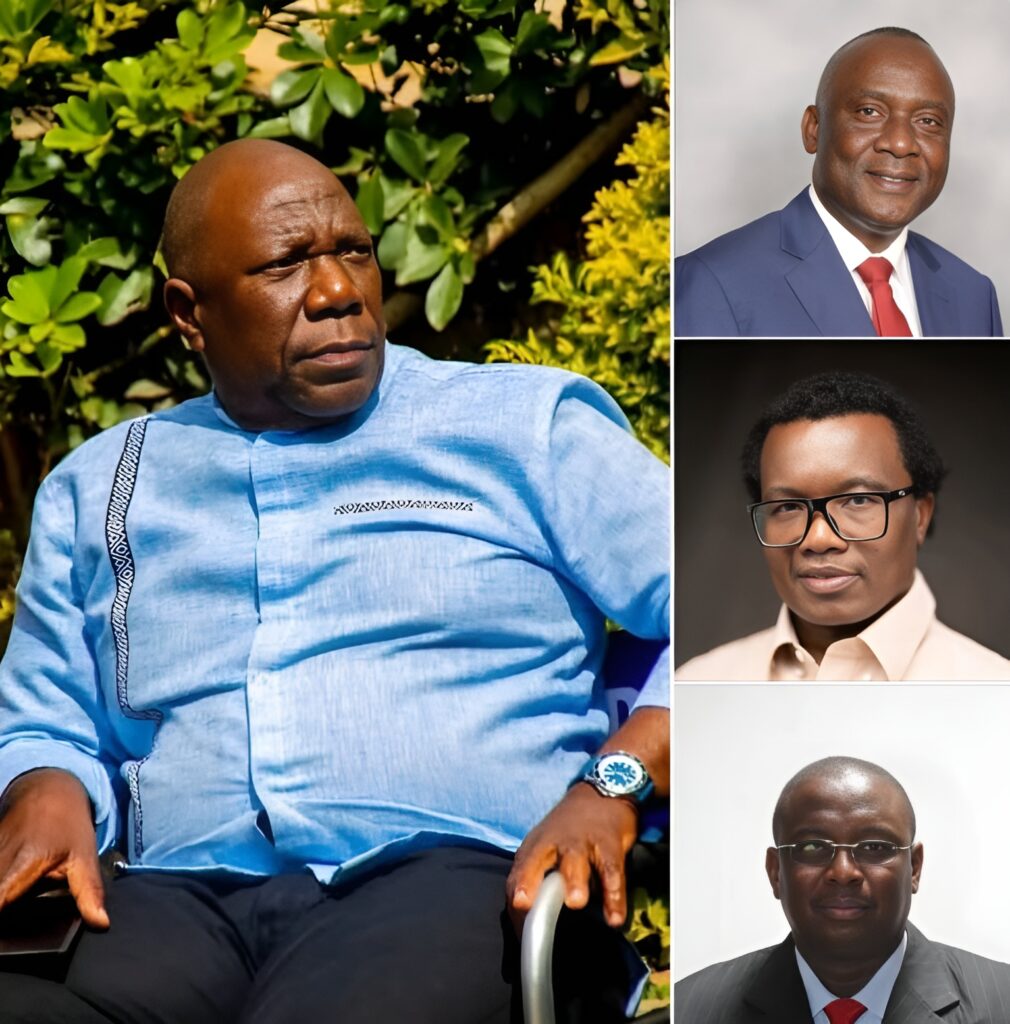

By all accounts, the political landscape of Malawi just took another dramatic turn when former Vice President Khumbo Kachali opted to submit September elections nomination papers as running mate to former President Joyce Banda under the People’s Party (PP) banner.

With this move, Kachali not only jolted the foundations of the much-hyped Northern Region Alliance Block but also effectively removed the last thread of credibility and influence holding that alliance together.

For months, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) had been banking on a coalition with a unified Northern political front to present a regional counterweight to the ruling Malawi Congress Party (MCP).

The Northern Region Alliance Block was marketed as a united regional front, comprising AFORD’s Enoch Chihana, Kachali under the Freedom Party (FP), National Development Party (NDP) led by Frank Mwenefumbo, and the Solidarity Alliance of political novice Victor Modhlopa.

The Block projected itself as a regional kingmaker, with aspirations to command a decisive share of the vote in the upcoming September polls. However, without the stature, experience, and grassroots clout of the former vice president, this alliance now looks more like a loose collection of political lightweights grasping for legitimacy.

The idea of a united Northern front is not new. Since the return to multiparty democracy, the Northern Region has oscillated between mainstream political parties, often seen as the swing region in Malawi’s tripartite political geography.

Despite producing sharp thinkers, passionate activists, and several technocrats, the region has struggled to consolidate its voice into a singular, sustainable political movement. The reemergence of AFORD in the 1990s under Chakufwa Chihana once held promise, but factionalism, poor strategy, and weak leadership saw its decline.

With the September elections approaching, the DPP sought to rekindle that dream by forging an alliance with Northern-based parties. However, without a compelling central figure to rally around, someone with national name recognition and genuine support in the region, the alliance seemed aspirational at best.

Khumbo Kachali was the only credible unifying figure within the Northern Alliance. His departure leaves the bloc stripped of gravitas.

Kachali’s decision to partner with Joyce Banda again may seem regressive to some, but politically, it is an astute move.

More importantly, Kachali’s move avoids the trap of tying himself to the increasingly factionalized and reputation-damaged DPP. The DPP’s entanglement with questionable characters like Alfred Gangata and Norman Chisale, and its slow-motion implosion due to power struggles and lack of a coherent campaign message, make it an unstable ship. By aligning with PP, Kachali retains independence, influence, and insulation from the tainted DPP brand.

From a strategic standpoint, the DPP’s entire regional alliance plan now lies in shambles. Their intent was clear: co-opt the North by packaging it as a unified block and have it fall in line behind a DPP presidential candidate. This arrangement was meant to compensate for the DPP’s waning popularity in the Central Region and maintain its Southern dominance.

But by putting faith in minor political players like Enoch Chihana, whose AFORD is now a shadow of its former self, and Frank Mwenefumbo, a political journeyman with no consistent constituency, the DPP erred by overestimating their influence.

Victor Modhlopa, the third leg of the alliance, is a political novice with minimal public engagement or political infrastructure. Their combined force, even with funding, lacks the magnetic pull to deliver votes.

Kachali’s departure essentially strips the alliance of its only serious statesman. It also sends a strong message to voters in the North: the alliance is not a genuine vehicle for regional progress but a DPP survival tactic wrapped in tribal packaging.

For years, politicians have romanticized the idea of a monolithic Northern vote, but history does not support this. The region is fiercely independent and ideologically diverse. Northern voters are less swayed by patronage and more by ideas and credibility. By staging alliances that seem purely transactional, parties like the DPP risk alienating the very electorate they hope to court.

What Kachali’s departure exposes is the hollowness of the Northern Alliance’s core proposition.

Without a cohesive ideology, a clear agenda, or a roadmap for how the region’s challenges would be addressed through the alliance, the bloc’s foundation was fragile. Kachali likely saw the writing on the wall and made a pragmatic exit.

Kachali’s decision now places the DPP in a political quandary. Bereft of serious allies in the North, the party faces the daunting task of defending its Southern base while trying to make inroads in the Centre. The North, meanwhile, becomes more competitive, with MCP, UTM, PP, and independents now having a freer hand to woo voters.

Joyce Banda’s People’s Party, bolstered by Kachali’s return, may not win many seats, but they could siphon off just enough votes to prevent a DPP resurgence.

In closely contested constituencies, a few hundred votes can tip the scales. Kachali’s influence in parts of Mzimba and Nkhata Bay, for instance, cannot be discounted.

The bigger danger for the opposition as a whole is the increasing fragmentation. With UTM, PP, and now what’s left of the Northern Alliance all running their own races, vote-splitting could end up benefiting the MCP which is maintaining a solid ground game.

For the North, the disintegration of the alliance is a missed opportunity to negotiate as a bloc.

Critics may accuse Kachali of opportunism, but in truth, his move might have spared him the embarrassment of being used by the DPP only to be discarded after the elections.

His presence on the PP ticket ensures that he remains a national player, one who can stake a claim in the political discourse and potentially negotiate future positions from a place of strength.

Unlike the others in the alliance, Kachali has a political resume, former Minister, former VP, party president, and a demonstrated ability to win votes. His strategic withdrawal from the alliance is as much about self-preservation as it is about disavowing a project that had little chance of success.

With Kachali gone, the DPP-Northern Alliance is effectively dead on arrival. It lacks credibility, leadership, and voter trust. More critically, it underscores the failure of regional political engineering driven by personality cults and electoral arithmetic rather than genuine development plans and ideological cohesion.

For the Northern Region, this is yet another moment of political disillusionment. The promise of a united voice has once again been sacrificed at the altar of personal ambitions and poor planning.

For the DPP, the collapse of the alliance should serve as a wake-up call that Malawi’s politics has evolved, regionalism alone can no longer win elections without substance, vision, and inclusive leadership.

The race for September just became more unpredictable.