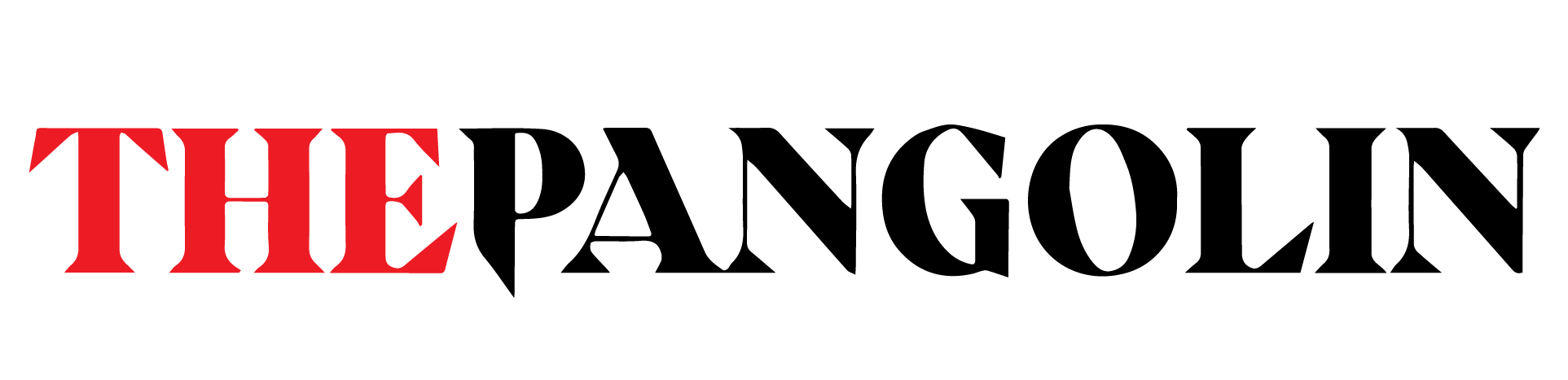

When Minister of Trade Engineer Vitumbiko Mumba, a bright, young firebrand and an aspiring Member of Parliament for Mzimba Central, took to Facebook to announce his resignation from the Malawi Congress Party (MCP) National Executive Committee (NEC), the statement sent political tremors across the landscape.

Mumba’s resignation is not just an isolated protest, it is a political indictment, a searing spotlight on the rot festering within the ruling party just three months before the September 2025 general elections.

Mumba, in his public explanation, stressed that he remains an MCP member, loyal to President Dr. Lazarus McCarthy Chakwera and pointed his resignation to “’man-made, small-mega battles’ aimed at ‘kuthana’ (destroying each other), a NEC dominated by handclappers who cannot even question anything.”

He also pointed out on the deliberate exclusion of those who invested in the party’s democratic processes.

His words echo a growing disillusion within the MCP base. Disillusion not with President Chakwera, but with party functionaries hijacking the machinery for personal and factional ends.

At the centre of this internal decay stands one man: Richard Chimwendo Banda, the party’s Secretary General.

For all the optimism that greeted the victory of the current administration in 2020, the MCP has squandered much of its goodwill. The party had a clear path to consolidate power and get a majority victory in September, but all seems to be lost.

With the opposition in disarray and its strongest electoral partner gone, the September elections are, in all practical terms, for MCP’s to lose.

And lose it they might, not because the opposition is strong, but because the MCP is busy destroying itself from within.

Chimwendo Banda has transformed the Secretary General’s office from a strategic engine into a factional battlefield.

His mission appears less about winning elections and more about eliminating internal rivals who could pose a threat to his own ambitions post-Chakwera. Alongside him are his regional lieutenants Regional Chairpersons for North-South Joseph Chavula and Eastern Region Foster Ntandama, whose actions are turning these two regions into chaotic battlegrounds.

Mumba’s departure is no accident. As one of the most energetic and effective young leaders in the North, he had become a symbol of MCP’s growing appeal in a region once skeptical of the party.

But instead of nurturing that momentum, Chimwendo Banda and his Northern surrogate, Chavula, worked tirelessly to sideline Mumba, manipulating the primary elections in Mzimba Central to impose a virtually unknown figure, Adamson Kuseli Mkandawire.

The aim? To weaken Mumba’s local and national standing and clear the path for total control by Chimwendo Banda’s loyalists.

But this isn’t just petty politics. It’s strategic suicide. If the MCP can’t protect its few rising stars in the North, it has no chance of expanding its influence in the region. Voters will not reward betrayal and confusion.

The situation in the Eastern Region is even more toxic. Ntandama, is at the heart of a growing scandal after it emerged he received MK87 million from his close friend UDF Patron Bakili Muluzi. The mission? Sabotage MCP from within by fielding weak candidates and convincing strong ones to switch allegiance or withdraw entirely.

The results are already visible. Atupele Muluzi, smelling blood, has emerged from political dormancy to loudly declare that Machinga, Mangochi, Zomba, and Balaka are UDF territories. He isn’t bluffing, he is counting on MCP’s internal implosion to hand him a regional revival.

And what has Chimwendo Banda done? Nothing. Worse still, insiders allege that when President Chakwera confronted Ntandama at Chikoko Bay over his dealings with Muluzi, the regional chairman casually admitted he “does business” with the former president—a relationship he never once declared to the party.

That MCP allows such a compromised figure to still hold a regional chairmanship speaks volumes about the rot at the top.

Make no mistake: this election is MCP’s to lose. The opposition, particularly the DPP, is weak, fractured, and suffering from a severe credibility crisis.

Arthur Peter Mutharika remains the DPP’s torchbearer, but he is an aging leader with diminishing public appeal. And worse still, there are real public fears that should he win, the real power behind the presidency will be Norman Chisale, a man whose reputation is synonymous with impunity and authoritarianism.

That the MCP might hand power back to the DPP under such circumstances is almost unfathomable, yet very possible, if it continues on its current path.

And what of Dalitso Kabambe. The UTM candidate might be a technocrat with a sharp resume, but he’s a novice in real-world politics. More damningly, he faces an impossible math problem to surmount before he really means anything on the national political stage.

Let us look at the simple mathematics that Kabambe himself is also probably failing to understand and feels he is there to even think of facing it alone, without an alliance, in September.

In 2019, late Dr. Saulos Klaus Chilima polled 21% of the national vote as a presidential candidate. Yet in that same election, his UTM only managed to send a handful of MPs to Parliament, just 2% of the total house. That tells you one thing: Malawians supported Chilima the person, not necessarily his party.

Now that Chilima is gone, the 21% is up for grabs, but not inherited. Kabambe must first elevate UTM from 2% to 21% just to retain the 2019 status quo. From there, he would still need to push toward the 50%+1 mark to win the presidency outright.

That’s a near impossible task for someone with no mass following, no track record of campaign charisma, and no clear political base.

What makes this unfolding drama even more tragic is that President Chakwera, by all accounts, remains committed to fairness, unity, and national transformation. But he is increasingly surrounded by individuals pursuing personal survival over party growth.

Chimwendo Banda, once hailed as a rising star in MCP, has now become a liability. Instead of cementing party structures, he is hollowing them out, replacing seasoned political warriors with “handclappers,” as Mumba aptly described them.

The SG has turned NEC into a chamber of silence. Now, this is also interesting: 80% of MCP’s NEC are co-opted members who never even expressed interest to contest during the convention or paid nomination fees. Meaning this 80% was brought in just because there were Chimwendo Banda’s hand clappers who can now not turn to question anything.

These are not democratic values; they are signs of a party being reduced to a fiefdom.

The September elections are around the corner. The MCP still has the upper hand, but time is running out. The public is not blind. They can see the internal chaos. They know that Chakwera is being undermined by those closest to him. They hear the voices of whistleblowers like Mumba and wonder: if this is how MCP governs itself, how will it govern the country going forward?

It’s not too late; but it nearly is.

MCP must urgently purge itself of these factional interests. It must neutralize saboteurs like Ntandama, reign in undemocratic fixers like Chavula, and put an end to ChimwendoBanda’s vendetta politics. If it doesn’t, it risks doing the unthinkable: losing an election that should be theirs to win.

Vitumbiko Mumba’s resignation is a warning. It is the clearest sign yet that the MCP, instead of uniting and expanding, is shrinking into an echo chamber of fear and fealty.

If President Chakwera wishes to preserve his legacy, and MCP hopes to retain power, he must listen to his wounded lieutenants. Because in the end, it won’t be the DPP, the UDF, or Kabambe that topple the MCP. It will be Chimwendo Banda along his surrogates Ntandama and Chavula, and his politics of betrayal.