Nthalire, in the remote highlands of Chitipa, is not the kind of place you stumble upon. It is 120 kilometres from both Chitipa Boma and Rumphi Boma, linked only by an earth road that has remained stubbornly rough for all of Malawi’s 61 years of independence.

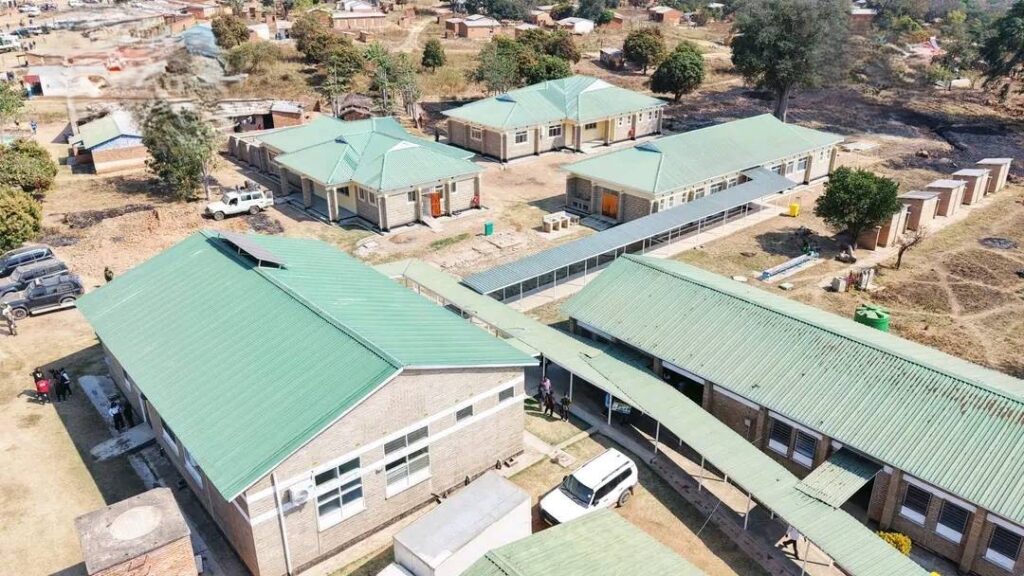

Yet on this week’s visit, the President of the Republic of Malawi Dr. Lazarus McCarthy Chakwera stood here, shook hands with the people, and cut the ribbon to open a magnificent new community hospital—complete with a functional theatre, laboratory, labour ward, mortuary, and separate male and female wards.

The symbolism is hard to miss. In a country where leaders often treat rural and remote communities as afterthoughts, Dr. Chakwera went where the road is bad, the distance is punishing, and the politics are often written off.

This was no ordinary whistle-stop campaign tour. It was a deliberate trek into a forgotten corner of Malawi.

Here’s the kicker.

Nthalire is where the presidential seal has been absent for years. No sitting president had set foot here in three decades, not since Dr. Bakili Muluzi last visited in 1995.

These facts alone would have made the trip newsworthy.

But what Chakwera’s visit revealed goes far beyond symbolism. Since 2020, Dr. Chakwera’s administration has constructed two health centres and now this community hospital within the Nthalire catchment area.

And the more politically telling and intriguing fact is this. Dr. Chakwera had to sleep over in this small remote town. He is the first Head of State in Malawi’s history to sleep over in this northern district during a working tour, a symbolic act of presence in a district that has long complained of being seen but not heard.

For a community historically excluded from even the most basic of state attention, this is an acknowledgment that they exist, that they matter, and that government can still remember its duty to the peripheries.

Nthalire was designated a rural growth centre at the same time as Neno. Neno eventually became a district; Nthalire did not. The difference? Neno lies in the Southern Region, the political turf of every democratic-era president before Dr. Chakwera.

This Northern Malawi’s rural growth centre, in contrast and like others in the region, was left to fade quietly from the national agenda. Dr. Chakwera’s presence in Nthalire is therefore not just another campaign stop; it is an act that disrupts a decades-long pattern of uneven political geography.

In modern Malawian politics, it’s one thing to talk about inclusivity from a podium in Lilongwe, and quite another to drive over 100 kilometres of bad dusty road to keep company with communities history forgot.

Dr. Chakwera’s decision to spend the night in a Northern district speaks to a style of leadership that values physical presence as much as policy.

This is the work of a servant leader. To go where it is inconvenient to go, to listen where no one else is listening, and to deliver services where the political calculus says there are “too few votes to matter.”

Let’s not pretend that there is no campaign logic here. With elections looming, rural visits are a staple of political strategy. But there is a difference between a photo-op in a district headquarters and a full day plus a sleep-over in a place like Nthalire.

This is political outreach layered over genuine state investment, and it is the kind of hybrid that can blur the line between campaign and governance in the best possible way.

For Nthalire, the hospital means mothers will no longer travel dangerous distances to give birth. Patients will no longer be ferried for hours in emergencies. And the community has a tangible reason to believe the presidency cares.

For Malawi, it’s a reminder that development must not be dictated by proximity to the capital or historical accident. Dr. Chakwera’s Nthalire visit challenges future leaders, regardless of party, to measure themselves not by how many rallies they hold in the cities, but by how far they are willing to go for the people who rarely make the headlines.

For years, presidential visits to the Northern Region have been the political equivalent of airport layovers with convenient sleep overs at the State Lodge in Mzuzu City.

The presidential playbook in the North has been painfully predictable. Land in Mzuzu; lay a foundation stone on a non-existent project; hold a rally at Katoto ground; have a rest or sleep at the State Lodge; fly back to Lilongwe or Blantyre the following morning.

Dr. Chakwera’s road trip to the literal end of the tarmac, and then beyond it, upends that pattern. It’s the political curveball no one saw coming, and in a campaign season, it might just be the kind of ground game that forces opponents to rethink the North not as a backdrop, but as a battleground.

The message that Dr. Chakwera has sent will surely resonate beyond Chitipa, playing into a broader national narrative about inclusion and the geography of power.