As the Malawi Congress Party (MCP) gears up for critical September elections with efforts to spread its wings and reach across the country, a dangerous internal storm has been brewing—one that could cost the party not just seats, but its credibility and political momentum in the eastern and southern regions.

What initially appeared as an isolated concern in Zomba Chingale over manipulated primary elections and intimidation of candidates has now expanded into a full-blown internal political treachery, sabotage and betrayal.

At the centre of the turmoil stands Foster Ntandama, the party’s Eastern Region Chairman, who is now accused of working in covert alliance with United Democratic Front (UDF) patron and former President Bakili Muluzi to systematically sabotage the MCP from within.

According to highly placed sources within the MCP, Ntandama is believed to have received MK86 million from Muluzi to engineer a stealth campaign aimed at weakening MCP’s parliamentary bids across the Eastern Region.

The strategy? Ensure that only weak, easily defeatable candidates win MCP primaries, and coerce or entice strong contenders to either withdraw or defect—preferably to the UDF. Some candidates reportedly received threats from operatives linked to Ntandama’s camp, while others were offered cash to abandon their bids.

This is not politics. This is betrayal dressed as strategy.

What makes this scandal even more revealing and dangerous is the figure of Richard Chimwendo Banda, the MCP’s Secretary General and one of President Lazarus McCarthy Chakwera’s most trusted lieutenants.

Chimwendo Banda and Ntandama share a long-standing political relationship. In fact, many insiders suggest that Ntandama’s rise within the party’s Eastern Region structures has been facilitated—and protected—by Chimwendo himself.

The Eastern Region chairman has reportedly benefited from strategic insulation at the national level, particularly when complaints against his conduct have been raised by party members in Mangochi, Zomba, and Machinga. These grievances have largely gone unanswered, fueling speculation that Ntandama operates under Chimwendo’s political patronage.

It is this connection that has now placed Chimwendo under a spotlight—not only for his silence in the face of mounting allegations against Ntandama, but also for his own increasingly controversial behaviour in party affairs elsewhere in the country.

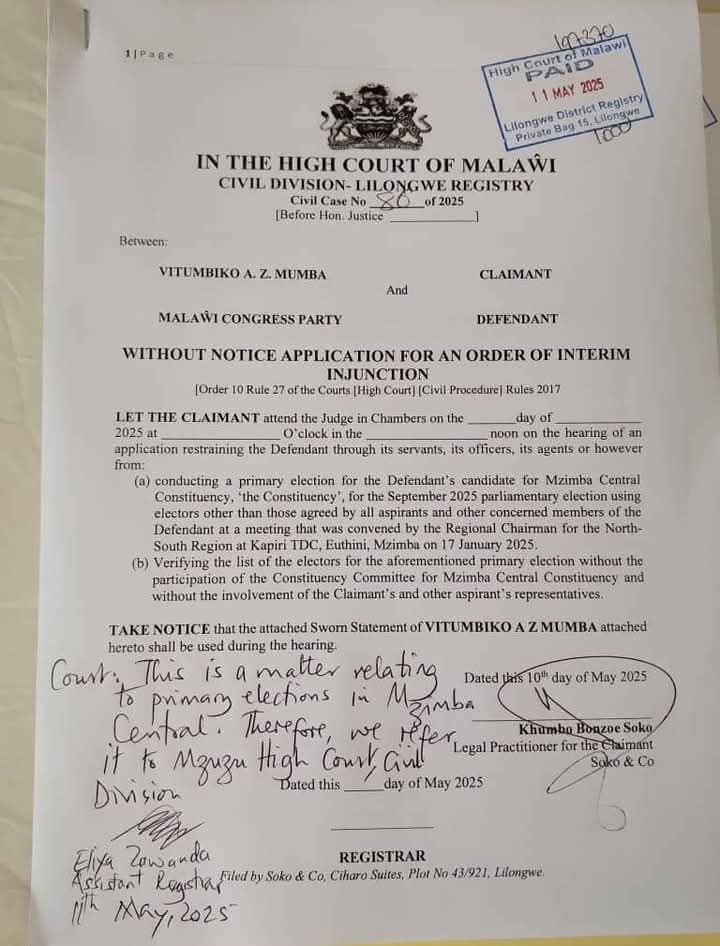

In the Northern Region’s Mzimba Central constituency, Minister of Trade Vitumbiko Mumba has publicly accused the MCP Secretary General of electoral manipulation during the party’s primaries in the area.

In a letter to the party leadership, Mumba decried the “hijacking” of the electoral college—alleging it had been stacked with non-party loyalists while legitimate, long-serving area chairpersons were sidelined.

Mumba, a rising voice within the party, views this as a calculated attempt to derail his election bid and force him into political exile. The implication? That a pattern of gatekeeping is being used to push out independent-minded voices, not just in the South but even in the party’s Northern footholds.

Mumba was not alone. Former MCP Secretary General Eisenhower Nduwa Mkaka nearly lost his re-election to represent the party in Parliament after September.

The interferences escalated tensions in several constituencies, leading to divisions among local party structures and sparking outrage among youth leaders and regional officials who view Chimwendo’s actions as undermining party unity. Several local leaders see this as part of a larger pattern—one in which Chimwendo is creating factional loyalties within the party to position himself for a post-Chakwera MCP.

“Chimwendo is playing a very dangerous game,” said one senior MCP official in the North. “What he’s doing in Mzimba and other constituencies is exactly what Ntandama has been accused of doing in Mangochi and Zomba—with Chimwendo’s blessing.”

If Chimwendo is indeed backing rival candidates, the implications are dire. It suggests a broader agenda of internal control and kingmaking, one that threatens to destabilize the party’s electoral performance by replacing winnable, established candidates with loyalists—regardless of their local popularity or experience.

As Ntandama’s alleged misdeeds become public, questions are still mounting: How much did Chimwendo know? Why has he remained silent while credible allegations pile up? And more importantly—can the MCP still claim to stand for transparency and accountability when its top campaign strategist is politically tied to the man accused of tearing the party down from within?

Taken together with his ties to Ntandama and the sabotage playing out in the East, the North and other constituencies, Chimwendo’s conduct raises serious questions about the centralization of power within the MCP and the fragility of its internal democracy. Rather than empowering regional and local structures to select the best candidates, the current trend appears to favour political interference from the top, with strategic calculations taking precedence over grassroots consensus.

In all cases, Chimwendo has remained conspicuously silent. But with internal primary battles now turning into loyalty tests, the party’s national cohesion is under serious strain. And that, more than anything, could be the MCP’s undoing heading into the September elections.

Malawians may ask: If the MCP can’t manage fair primaries in its own ranks, how can it promise democratic credibility to the nation?

Several party insiders believe that Chimwendo’s silence is strategic. “He can’t distance himself too quickly,” one said. “Doing so would expose just how much he allowed Ntandama to operate unchecked.”

If the allegations against Ntandama are true, and if Chimwendo knew—or turned a blind eye—then the scandal is no longer just about one rogue chairman. It is about an entire wing of the MCP that is willing to trade winnability for personal influence.

Time is running out. The September elections are fast approaching, and the Eastern Region—already historically difficult for the MCP—is turning into a potential graveyard for its ambitions.

Nowhere is this internal sabotage more apparent than in Zomba Chingale, where the local District Chairman—reportedly acting under Ntandama’s directive—has been accused of rigging the primary elections process. Sources on the ground say that weaker candidate was handpicked, while stronger aspirants were either threatened or bought off.

Several well-positioned candidates have since withdrawn their intentions to run, citing “unfair treatment”; “an unsafe political environment” and the growing dominance of “money and connections” over merit and public service.

The Southern and Eastern regions are already tough terrain for the MCP. Instead of nurturing grassroots loyalty, the party seems to be allowing gatekeeping and intimidation to dictate who gets a ticket. This undermines the very reason the MCP had started to make notable gains in these regions: its promise of inclusive, clean politics.

The MCP must now ask itself some serious questions: What is the cost of internal loyalty when it compromises national strategy? Can the party afford to protect Ntandama for the sake of old political alliances? And is Chimwendo’s silence evidence of complicity—or just poor judgment?

At stake is more than just a few constituencies. The MCP’s entire southern and eastern strategy is on the line. If voters perceive the party as internally corrupt, unwilling to deal with rogue elements, and more concerned with internal patronage than national reform, they will walk away. And they will not walk alone.

Moreover, this scandal risks fracturing the party’s already delicate internal unity. Tensions between the Central Region powerbase and the party’s ambitious regional structures in the South and East are real. Many young party loyalists in the East who joined under the promise of renewal and democratic inclusion are now disillusioned.

As one frustrated youth leader in Machinga put it: “We thought we were building a new MCP. Instead, it’s the same old politics—just in red.”

If President Lazarus McCarthy Chakwera and the MCP leadership want to salvage this situation—and their credibility—they must act decisively.

That means: suspending all rogue officials immediately, regardless of position in the party, pending a full investigation and publicly clarifying Chimwendo Banda’s relationship with Ntandama and the nature of their political alliance.

The MCP should further allow truly open, transparent processes of coming up with candidates across the East and South, with independent observers; empower grassroots structures to vet candidates instead of leaving it in the hands of district or regional chairs; and rebuilding trust through clear, public communication from the President himself.

As it is, MCP’s greatest threat is not the DPP or UDF — It is itself. It is people like Ntandama and his pay master Chimwendo Banda.

With elections looming, the MCP should be consolidating gains and capitalizing on its incumbency. Instead, it finds itself shackled by internal sabotage, betrayal, and strategic complacency. If it fails to address these internal cancers now, the consequences will be devastating—not just in September, but in 2030 when the post-Chakwera transition begins.

President Chakwera’s leadership has long been associated with integrity, reform, and restoring public trust. But his legacy will also depend on how he handles enemies from within. The MCP is at a crossroads. It can either clean house or continue enabling those who are tearing it down from inside the tent.

Malawians, including MCP diehards, are watching. And come September, they will remember.